I'll come right out and kill the suspense by admitting that I think The One Ring is one of the best roleplaying games I've ever read or played. When I first saw it, I had the impression that it was a relatively simply system, possibly because it only had three stats or something like that. But make no mistake, The One Ring is a quite crunchy system, although elegantly so. I'll eschew describing the whole system (as some reviews are wont to do), and instead touch on some of my favorite mechanics.

First of all: Travel. How. The. Hell. Has there never (to my knowledge) been a system with a travel system before!? Fantasy games are all about schlepping your butt across the map and back again, and yet there are no systems for dealing with the implications of such strenuous activity, beyond random encounter tables. This is astounding.

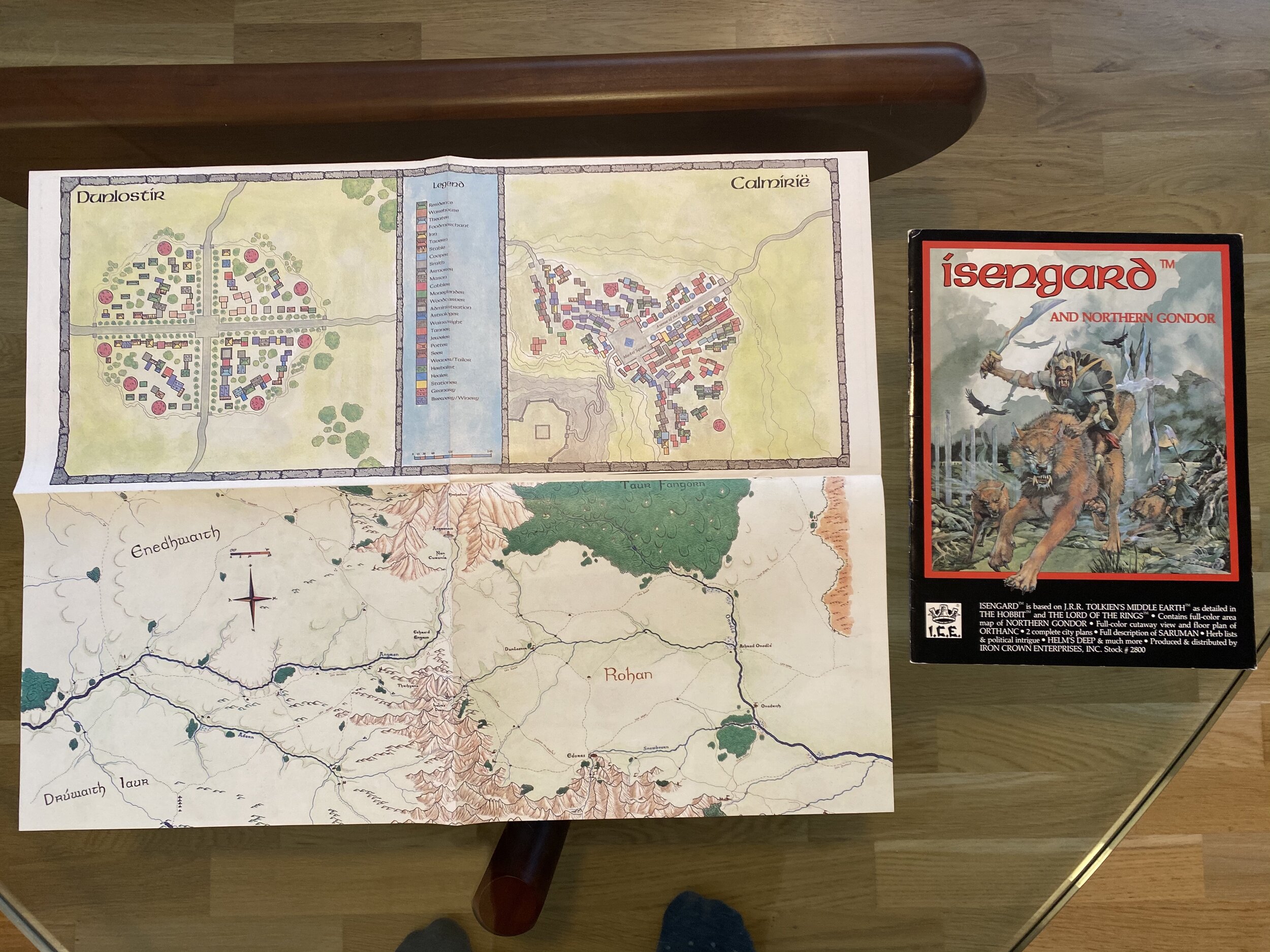

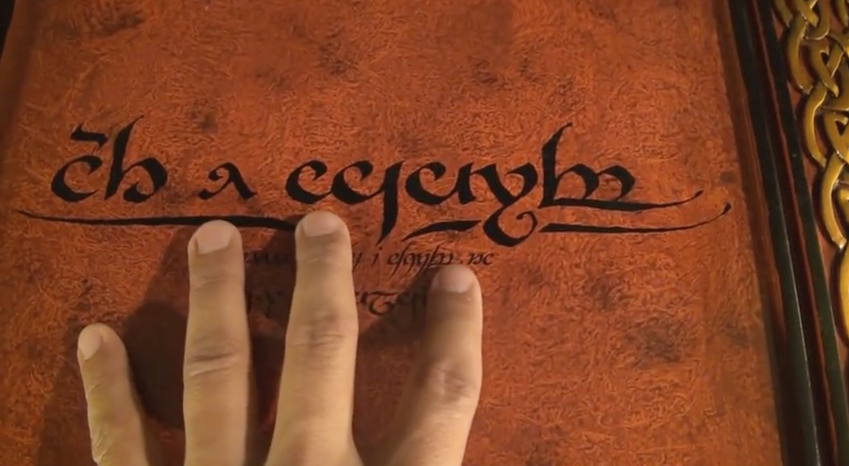

Travel is at the core of Tolkien's writings, and therefore at the core of The One Ring. In short, the game comes with two old-looking maps (the old version did anyway, in the new one they are printed on the inside of the front and back covers instead, not as nice, but it works) of Wilderland, one for the players and one for the Loremaster. The players use theirs to plan a route, and the Loremaster uses his, which has hexes, colors and symbols for terrain difficulty and 'corruption of the land', to calculate the length of the journey, and how many Travel and Corruption rolls the company is to be submitted to. There are rules for traveling in the summer or the winter, for going upstream or downstream and for using horses (although there are currently no official rules for using horses in combat).

And here's the elegant part: Companions have a certain level of fatigue they can endure. This is affected passively by the equipment carried (armor, weapons, anything else substantial) and actively when you're fighting as well as of course when you travel.

The choices around what to carry, which routes to take when traveling somewhere (or indeed whether to travel at all!) as well as whether to attack that orc patrol or sneak past them, all intermingle and cause the company to make some at times hard choices around when to rest, and when to press on despite impending exhaustion, which can be truly deadly in this system.

Another great mechanic is the use of Hope as a resource the companions can drew from, and which replenishes itself over time, although not necessarily fast enough. Because at the same time the Shadow is corrupting their minds and hearts, and if you're not careful (or if you have no choice but to spend Hope), you may find yourself in a nasty bind before long.

Well, actually before long is relative. The system seems to have been made for long campaigns as it takes a while to get to the point where your character suffers any kind of permanent damage from his exposure to the darkness in the world. At times this feels like more of a hollow threat to the companions, but then someone gets careless, and before you know it they've ended up in a situation where they have to rely on their Hope, but doing so will bring them closer to the darkness. Good, good stuff.

As with Travel, social 'Encounters' are also systematized in The One Ring. Which is to say that such things as an audience with a king or ruler is an Encounter, whereas shooting the shit with Bob down at the inn probably isn't. While I've found it hard to properly work it into the game as written (I'm not sure my players understand it yet, even though we've gone over it a dusin times by now), it nevertheless adds a good set of guidelines as to how such encounters can unfold. In some cases the various companions' Standing and Wisdom or Valour as well as their race and how they chose to conduct themselves all play into how they are received by whomever they are encountering.

While I love the fact that skills are employed in Encounters in a quantifiable way, it's a hard line to walk. On the one hand the actual skills of the companions are meant to determine in a very direct way the outcome of the encounter, on the other the players themselves have a direct influence through what they say at the table. This of course is an age-old problem in roleplaying games, in which the player might directly contradict the character he or she is playing, and even if caught by the LM, it's not always easy (or desirable if the player delivered a great speech) to tell them "Well, you definitely don't say that; your character is supposed to be rude."

The solution of course is to have the players roll first, and talk second, but so far we've been unable to adhere to that order (old habits die hard I guess), although your mileage may vary.

So inevitably there is a lot of LM adjudication in the running of Encounters to make them work, and while I've personally run only pre-written adventures so far, I also imagine that it will be harder to do them justice if you're improvising them without any kind of prep-work. As usual, my best advice (for myself as well) is 'slow it down, set the stage', and it has a tendency to work much better.

There is one final mechanic that I was at first worried about, but which has shown itself to work quite well indeed, and that is combat Stances. The One Ring has no grid or miniatures as such, instead when entering into armed conflict, the companions (and only the companions, mind you) chose how they want to fight this round, whether they want to be Forward, Open, Defensive or Ranged. There are a number of rules governing what can be done when, but in short the more aggressive you fight, the easier you can hit, but the easier you are also to hit.

This along with how each Stance has a certain kind of action that can be performed (such as 'Rally Comrades' or 'Intimidate Foes'), works tremendously well, and with each weapon also having called shots, ensures that fighting doesn't have to become droll bash-fests. Although to be quite honest, they do sometimes...

And that's why the adversaries have special ability; to screw with the players. The archer who thought he was always out of reach in Ranged Stance? Meet the Warg, which has a special ability called Great Leap which lets him do what other adversaries cannot, and attack that pesky archer (and of course grabble him so the orcs can have a free run at his friends).

There is something quite pure about how this system's combat runs in a more abstract way, similar to many other non-D20 systems, while still maintaining some well-modeled mechanics that allow for interesting tactical choices to be made during a fight.

As mentioned previously, we play online using Roll20, and to ease the workload of the players and myself, I've devised various scripts to help us resolve combat quicker. This requires for me to use tokens to represent the enemies. This saves us (me, mostly) from having to figure out the Target Numbers for attacks (Stance + Parry Rating + Shield - Circumstantial Modifers; not too bad, but there is always a lot of 'what's your parry rating again?' going on at the table for things like that), and keeps the weapon stats close at hand at all times. It does however bring us a step closer to a miniatures-like world, and I'm starting to question whether it's really worth it, as the abstract world of combat offers so much more perceived danger. But that's for me to figure out, and a complete aside to this review.

One final thing to mention is how the game is split into Adventuring Phase and Fellowship Phase, Adventuring being the going about and slaying the things, and Fellowship being the part where the heroes retire to their sanctuaries and rest their sore bodies. Fellowship phases are a bit of a nebulous thing, as they can last anywhere from a couple of weeks to many months. The book on the one hand suggests that they can last up to three months, and on the other suggests that you run a single Adventuring Phase every year. But given that an Adventuring Phase is unlikely to last more than maybe a month or two at the extreme upper end... Well, it's just a bit confusing, and it causes an issue because while Fellowship Phases are the time when the companion is supposed to do all the other stuff that a companion does when not going about and slaying things, there are no rules governing the difference between having two weeks to do so, or ten months. Either way, you get a single thing you can do. Easy enough to adjudicate on many LMs would say, but if I wanted to adjudicate on such matters I would have written my own rules to begin with. And the issue here is exacerbated by the fact that so far my players have been uninterested in doing anything other than getting their Shadow Points under control. Maybe that says more about my players than about the system.

As of the time of writing, The One Ring has five expansions in print (all must-haves to be quite frank), each of them bringing something new to the setting as well as the rules. There have been new Cultures added, many Fellowship undertakings and such. And even at this point, it's beginning to be a little hard to track it all. There are fan-made PDFs floating around that keep track of these things, but I'd honestly love to have it all swept up into some 2nd Edition volumes for easier reference.

Summary

I love this game. It's evocative of Tolkien's writings, and the mechanical design is a huge part of this. The world of roleplaying has come a long way since I was last properly active, in the early- to mid-90s, and there are now a wealth of truly great system choices for roleplayers out there. But nevertheless The One Ring manages to sit at the very top alongside a precious few other games (Trail of Cthulhu would be one of my other choices), and that's saying something.

Buy this game.